Curriculum Vitae

Born in Kamen

Educational and extracurricular ceramics classes

Studied in Münster; simultaneously taught young people how to design ceramics

Professional activity in Düsseldorf and Münster

Freelance artist in Münster since 1996

From 2007, ceramic works combined with wire

Member of Sculpture Network, SingulArt

Privately owned art objects in Germany and abroad:

Great Britain, Netherlands, USA, Finland, Germany

Exhibitions and participation in exhibitions:

Münster, Mühlenhof, annually, 2000 to 2012

Essen Borbeck, Alte Kuesterei, 2009

Eppstein, 2010

Wolbeck, Atelier punkt, 2011

Bad Pyrmont, 2011

Iserlohn, Historische Fabrikanlage Maste-Barendorf, 2012

Sendenhorst, Lydia Brüll Gallery, 2013, solo exhibition

Dortmund, Westfalenhallen, 2015

Wolbeck, Rudi Fred Linke Gallery, 2015

Since 2018, permanent exhibition in own studio in Münster Wolbeck.

Borken, Artline und Open Art Gallery, 2020, 2022, 2023

Münster, Torhaus, 2024, solo exhibition

Münster, Erphokirche, 31.08.-28.09.2025, solo exhibition

Publications:

Tony de Kaper-van Aalst, Spitzen und Ton, Kantbrief, 2011

10 Jahre ART TO TAKE, Historische Fabrikanlage Maste-Barendorf Iserlohn, 2013

Westfalium Issue No. 84 / Winter 22

Artistic statement

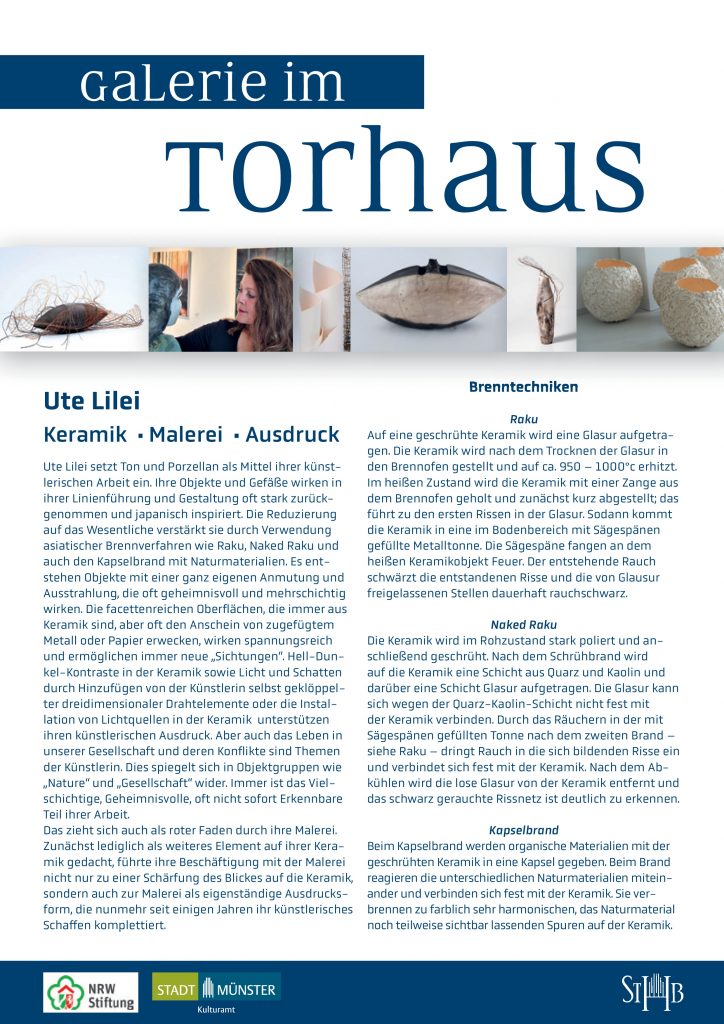

Ute Lilei prefers clay and porcelain for her artistic work. She uses these materials to give her objects form and expression. Influenced by the distinctive, minimalist aesthetics of Japanese ceramics, which are complemented by the firing techniques used by the artist, such as raku, naked raku, and capsule firing, she creates works of art that are new and unique in their appearance and ceramic expression. Her objects are characterized by a reduction to the essentials and a restraint in color. The artist often adds other elements to the ceramics, such as translucent wire structures—which she creates three-dimensionally to fit each object perfectly—or integrated light sources. Materials that seem almost contradictory merge into a new, more advanced unity.

The representation and amplification of light, the contrasts between light and shadow, transparency and opacity, the elimination of the contrast between heavy ceramics and light wire—can the light wire support the heavy ceramics? – the contrast between light, fanned-out clay elements that look like burnt paper and smooth, heavy, shiny ceramics are the subject of the artist's work. The objects appear mysterious due to their surface and change their appearance as the daylight changes. New facets are constantly revealing themselves. They invite the viewer to engage with the objects again and again, leading them into a special world of objects.

The firing process—the ceramics bear the traces of smoke from the fire—creates random textures and color effects, which are deepened and enhanced by the wire compositions. This opens up endless possibilities for the artist to continue her experiments with ceramic materials. The surfaces of her ceramics tell stories that are further spun out and condensed by the wire elements. They invite us to trace them. Sometimes the traces on the ceramics seem to date back to times long past, while other objects express the artist's thoughts on political and social issues. Currently, her artistic work reflects the changed perception of the environment and the consequences of our actions.

In her careful and intuitive handling of clay, an intense communication and dialogue takes place between the artist and the material she is working with, making it almost visible to the viewer in her objects.

Ausgegrenzt, 2012 | Ceramic (capsule firing) | Stainless steel wire | Acrylic plate | Marble | H 16 cm, W 49 cm, D 15 cm

Firing techniques

Raku

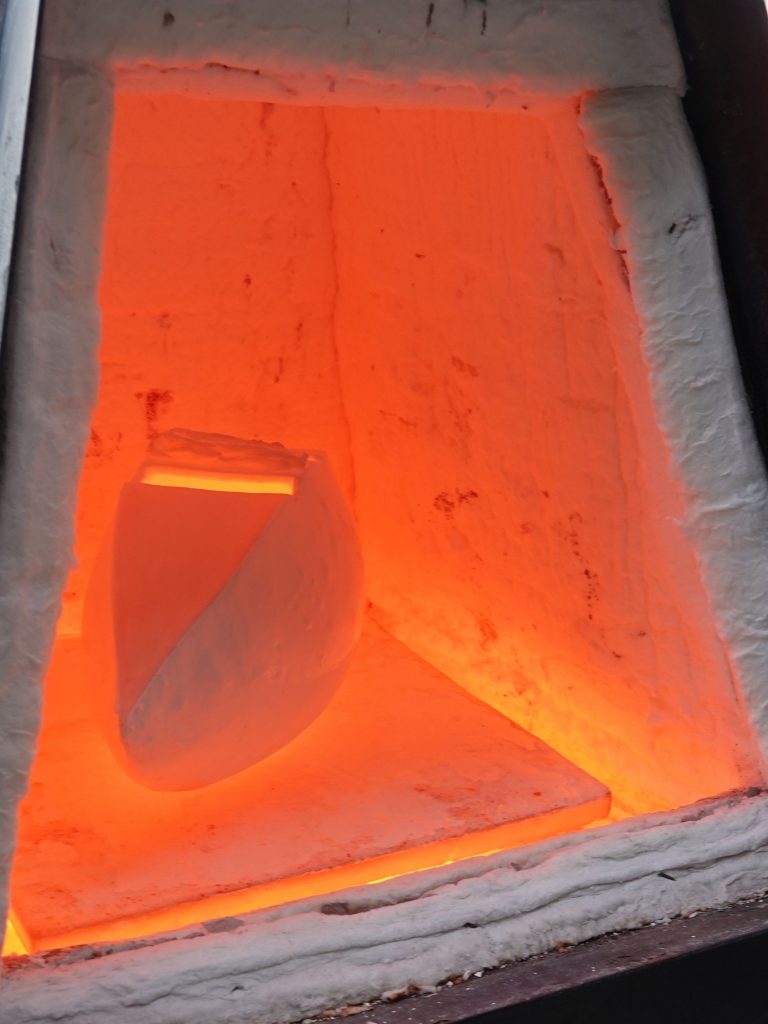

A glaze is applied to a bisque-fired ceramic. Once the glaze has dried, the ceramic is placed in the kiln and heated to approx. 950–1000°C. While still hot, the ceramic is removed from the kiln with tongs and set aside briefly, which causes the first cracks to appear in the glaze. The ceramic is then placed in a metal barrel filled with sawdust at the bottom. The sawdust catches fire from the hot ceramic object. The resulting smoke blackens the cracks and the areas exposed by the glaze, leaving them permanently smoke-black.

Naked Raku

The ceramic is polished thoroughly in its raw state and then bisque fired. After bisque firing, a layer of quartz and kaolin is applied to the ceramic, followed by a layer of glaze. The glaze cannot bond firmly to the ceramic because of the quartz-kaolin layer. By smoking the ceramics in a barrel filled with sawdust after the second firing – see Raku – smoke penetrates the cracks that form and bonds firmly with the ceramic. After cooling, the loose glaze is removed from the ceramic and the black smoked network of cracks is clearly visible.

Capsule firing

In capsule firing, organic materials are placed in a capsule with the bisque-fired ceramic. During firing, the different natural materials react with each other and bond firmly with the ceramic. They burn to form traces on the ceramic that are very harmonious in color and still allow the natural material to be partially visible.

‚Ton-Gespinste‘

Introductory remarks by Lydia Brüll, Sendenhorst, on the occasion of the opening of Ute Lilei-Dorn's exhibition on April 20, 2013 (translated)

Good evening, dear art lovers – I am delighted that you have once again found your way to my art studio.

I went on another journey of discovery and encountered the artist Ute Lilei-Dorn, inviting her and her extraordinary objects to my gallery. Dear Ute, I warmly welcome you and thank you for allowing us to share in your creative work for a few weeks.

Ute Lilei-Dorn provides the paradigm for how different materials of very different types and origins can be successfully combined. She works with clay and wire, creating an exciting relationship between these two materials in her artworks. Both are materials that accompany us in everyday life, but also in the art scene. Ceramics in the form of everyday objects such as bowls, plates, and cups, but also in the form of art objects—wire as an elementary component of everyday life, but also in the form of wire art.

The lawyer Lilei-Dorn lives and works in Münster. She felt drawn to art from an early age. What was once intended as a balance to her career has long since become her main occupation. Her art has become well known through her exhibitions in Bochum, Münster, Essen, Eppstein, Bad Pyrmont, Wolbeck, and the Netherlands.

The design of her objects is time-consuming and labor-intensive. Once she has a complete picture of the object in her mind's eye, made of ceramic and wire, she first creates a drawing. This is followed by three separate steps: she models her clay elements using the building technique. These are polished thoroughly in their raw state until they feel completely smooth, then they are bisque fired. This is followed by the finishing of the surface using the raku, naked raku, or capsule firing process. Raku and naked raku are two centuries-old Japanese firing techniques that have become very popular in the West. In both processes, glaze is applied to bisque-fired ceramics. Once the glaze has dried, the ceramics are heated in a kiln at 950-1000 degrees Celsius. While still hot, the ceramic is removed from the kiln with tongs and set aside briefly. This causes the first cracks to appear in the glaze. The ceramic is then placed in a container with sawdust and set alight. The smoke penetrates the cracks in the ceramic, creating unique marks on the surface.

The capsule firing process also yields interesting results. Here, the artist experiments with organic materials such as fruit, leaves, and horsehair. The bisque-fired ceramics are placed in a capsule with the materials. During firing, these leave a wide variety of color marks on the ceramic surface. The artist's ceramics alone are very sophisticated in their formal and color aesthetics and have a strong charisma of their own.

In the second step, the previously planned wire area is designed. A separate design (bobbin lace pattern) is created for each object. We combine the old handicraft technique of bobbin lace-making with the production of lace by crossing, twisting, or intertwining threads that are wound onto bobbins (wooden sticks). Lilei-Dorn uses bobbin lace, but modifies it for her work. To match the smoky or intense colors on the ceramic surface, she combines filigree wires made of copper, silver, stainless steel, or finely silver-plated or gold-plated Leonian threads, which she then bobbins flat or three-dimensionally. The use of more than 60 pairs of bobbins, which means more than 120 bobbins, is not uncommon in her work, the artist reveals. Some of the wire threads are as thin as a hair, but much stiffer than the usual bobbin lace thread. This carries the risk that they break easily, destroying the entire piece of lace and forcing the artist to start all over again.

In the third step, the ceramics are further developed into a new art form with the transparent, filigree, sometimes multicolored wire webs. Lilei-Dorn has thus found her own unique sculptural language for her works. The flexibility and malleability of the material influence the artist's creative decisions. If we look closely at the “clay webs” created in this way, each of the formal elements attracts our gaze and fascinates us with its details, while the artist creates visual references that fascinate us even more. This transforms the optical perception of the individual forms into further, flowing visual movements. Our eyes follow curves and vibrations. Calm and movement, rising and falling, light and dark set the accents. Where the light- and air-permeable wire mesh envelops the ceramics, or seems to be connected to them as if by chance, the “clay web” always appears like a field of energy. It seems to have an inherent urge to expand, to pour into the space, to flow further. When light comes into play, we not only see delicately glittering webs interwoven with light, but our attention is also drawn to the multitude of shadows cast by the artwork. The shadow, as the reflection of the object, is inseparable.

Lilei-Dorn gives her objects titles. For many art lovers, titles serve as the most important piece of information, enabling them to gain an understanding of the work, so to speak. However, a title not only helps to identify a work of art, it also becomes a carrier of meaning and has a considerable influence on the viewer's reception. In addition to the visual dimension, it always refers to an expanded linguistic/narrative dimension. This is used by the artist to convey certain aspects and steer associations in a particular direction.

Lilei-Dorn is aware of this fact. Certainly, she wants to use the titles to mediate between her works and their appropriation by the viewer, but she does not intend the title to inhibit the viewer's flow of associations. It is precisely in the tension between the work, the deliberately chosen title, and the viewer that she hopes to foster a broader dialogue. For each work has an impact on the viewer that is multi-layered in its interpretation and that each viewer will experience in their own way.

Lydia Brüll, Introductory remarks on the occasion of the opening of Ute Lilei-Dorn's exhibition on April 20, 2013 (translated)

Open House, April 30–May 1, 2022: Dialogue with an Object

Article from Westfalium, Issue No. 84, Winter 2022:

Text accompanying the exhibition in the Gatehouse 2024